The 30th day of May, 1868 is designated for the purpose of strewing with flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village, and hamlet churchyard in the land.

— John A. Logan, 3rd Commander in Chief of the Grand Army of the Republic

What is today Memorial Day began as Decoration Day by John A. Davis’ proclamation issued May 5, 1868. As the name and preceding excerpt suggest, Decoration Day was originally about beautifying the graves of men who’d died fighting the Confederacy in the bloodiest of American wars, just three years concluded. It wasn’t until 1971 that Memorial Day became the official name of the holiday.

There are three national cemeteries in Oregon. Yesterday, I visited all of them, and am happy to report the condition of the graves is good. Each one of the thousands of final resting places for veterans and their spouses is decorated with a small American flag. Memorial Day eve, Oregonians in family groups, couples or by themselves were placing flowers at the graves of loved ones.

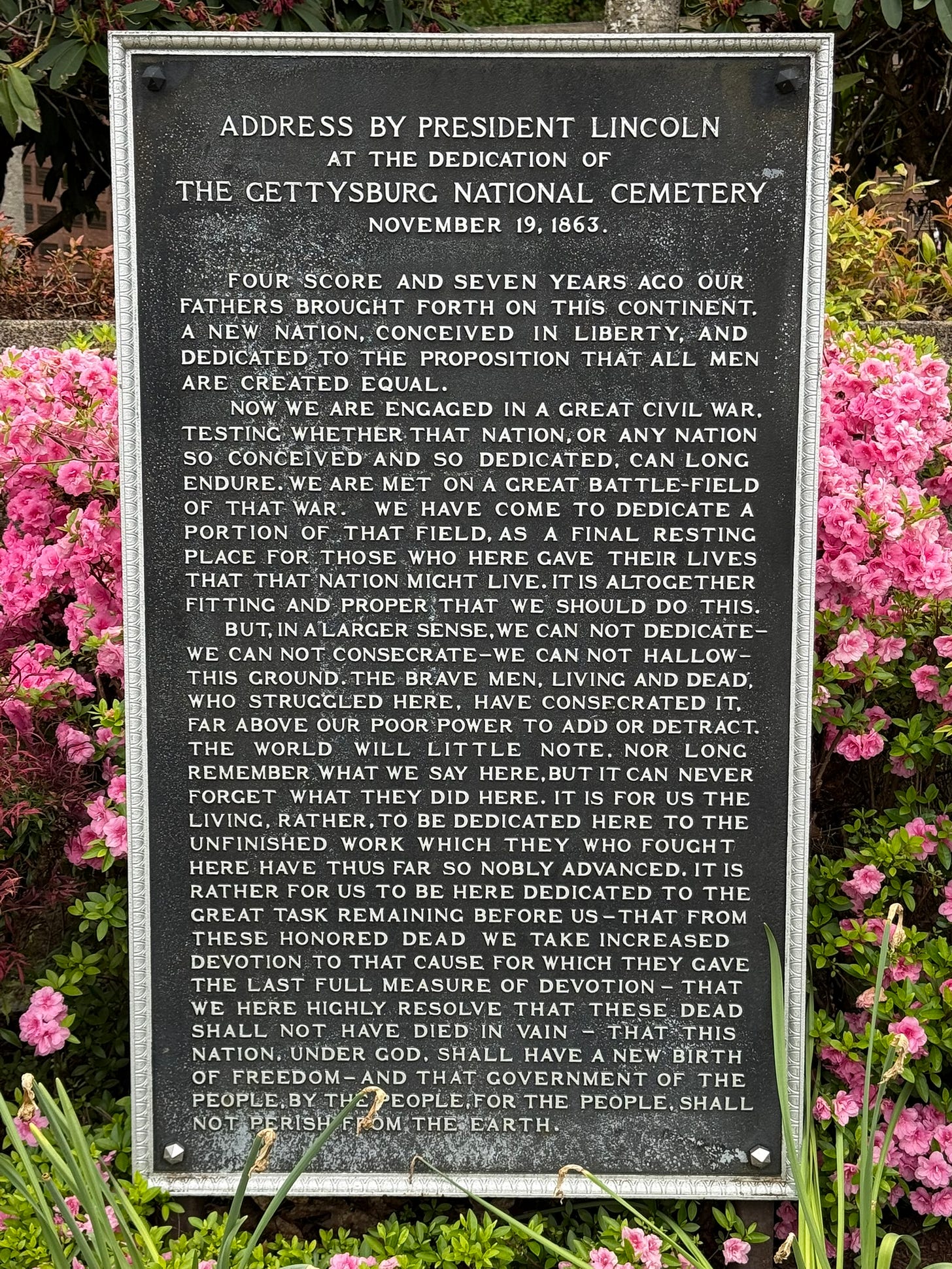

The cemeteries are oases. The largest, Willamette National Cemetery, atop Mt. Scott in southeast Portland, features a plaque with Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, in a city that five years ago abided the defacing and removal of a statue of its author, and still has not quite figured out how to put it back up.

And indeed, the cemetery ground at Willamette feels consecrated. A place of honoring a purpose surrounded by a place that rejects it.

Less than five years after Lincoln spoke those words in Gettysburg, Logan A. Davis wrote these in Washington,

What can aid more to assure this result than by cherishing tenderly the memory of our heroic dead who made their breasts a barricade between our country and its foes? Their soldier lives were the reveille of freedom to a race in chains and their deaths the tattoo of rebellious tyranny in arms.

There are Civil War veterans buried in Oregon’s national cemeteries. Some served, according to their headstones, in Oregon units. Most served in those of other states, many in the upper Midwest. When the Civil War ended, Oregon was but six years old, and many veterans brought their families west after the war to carve out a life in the bounty, and the beauty, abutting the Pacific.

They are buried in an historically illiterate state that recently deemed the name of the war in which they fought, not a reveille of freedom, but a stain unworthy of gracing a football game.

Roseburg National Cemetery is the smallest of the three, occupying about four acres next to some soccer fields at the periphery of town. In it, there is the grave of World War II veteran Donna-Mae Smith, making the audacious, and intentionally unchecked by this author, of being the first woman bugler in the U.S. Military.

Roseburg is an annex of the larger Eagle Point National Cemetery, just outside Medford. Eagle Point, like Willamette, is atop a hill, with commanding views of the southern Oregon landscape.

All national cemeteries are, by definition and intent, hallowed ground surrounded by unhallowed ground. This visitor was struck by how the Oregon national cemeteries are not just physical sanctuaries but moral, ideological portals to another place, another time, another frame of mind.

The people Oregonians have elected to represent us are acknowledging Memorial Day. I believe they mean it. It is natural to honor those who’ve died, particularly those who died in, or after, service to others.

But those who populate national cemeteries, and “every city, village, and hamlet churchyard in the land,” served not just their countrymen, but a purpose. That purpose was the sustaining of a unique kind of relationship between the governed and their government. Americans were born to govern themselves. America was born to protect their right to do so, a right that precedes and supersedes any authority of government.

When there are challenges to Americans’ birthright, the self-governed muster to defend it. In the case of the Civil War, they gathered to expunge the foremost American hypocrisy. There are many enemies of self-governance, foreign and domestic. And so we have national cemeteries.

Oregon’s trajectory seems ever-diverging from the principles uniting those we memorialize today. My state views the Americans living within its borders not as self-governing but as problems to be governed. It strives for and rewards dependence, for perceived dependence is the justification for the accumulation of power, the elevation of the govenment over the governed.

Particularly noticeable on Memorial Day, on which we honor those who did, Oregon is obsessed with what or who people are, not what they have done. America is not the greatest liberating polity in the history of humanity, but an instrument of oppression. Those who died in or following service to that instrument are yet another class of its witless victims.

But that lie is a slander against the thousands buried at Willamette, Roseburg and Eagle Point. America is the necessarily imperfect reveille of freedom for all humanity. Those who died in furtherance of the still-spectacular, still-unprecedented experiment in self-governance did something.

And what they did was good.

Seems Portland is much more focused on honoring George Floyd than the veterans who died serving the county…..

https://www.portlandmercury.com/blackout/2025/05/19/47783840/blackout-a-five-year-retrospective-on-portlands-racial-justice-movement

That was perfectly stated. My suggestion is that all Oregon State legislators be given mandatory military service, four years, in combat, then let them come home and try to spout off their nonsense about DEI.