Oregon's illegal immigrant Republican businessmen

Ing "Doc" Hay and Lung On carved success from the mining outpost of turn-of-the-century John Day

In 1839, Commissioner Lin Zexu, under direct orders from the Emperor of China, confiscated large quantities of British-owned opium in the southern port city of Guangzhou, setting in motion events that culminated with the 1952 death of a blind 89-year-old Chinese herbalist in a Portland, Oregon nursing home.

The sale, possession and use of opium was illegal in China, the government of which sought to deter the social fallout from widespread addiction to the drug imported from the British colony of India. The British had their own empire to fund and resented its trade deficit with China. It turns out the Chinese weren’t interested in buying much from the Brits other than opium. So, there was a large, illegal flow of opium into Guangzhu; some of it was seized by Zexu.

Angry at the insult, the British launched what would become known as the First Opium War, at the successful conclusion of which it gained access to Chinese ports for opium and other trade, as well as a longterm leasehold interest in Hong Kong, less than 100 miles from Guangzhou. For good measure, the British, joined by the French of all people, and Chinese fought a Second Opium War from 1856 to 1860, winning more European access to Chinese markets and more favorable trade terms.

Guangzhou was, in the the 19th Century as now, the capital of Guangdong Province, which hugs the southern coastline of China. The Opium Wars tore giant holes in Guangdong’s economy and society, creating a large surplus of men with few local prospects for work.

At the same time, America was bounding westward, spurred in part by the discovery of gold in first California and then Oregon and other western states. Mines and railroads to hasten the surge west needed workers, especially workers so desperate as to require lower pay than Americans from the east.

The confluence of Guangdong collapse and American opportunity led at least 300,000, almost all men, to leave the former for the latter in the in the mid-to-late 1800s. Some of those men made their way to the John Day River valley in eastern Oregon, where gold was discovered in what is now Canyon City just as the Second Opium War was wrapping up.

Ing Hay was born in Xiaping Village, Guangdong Province around 1862. Little is known of his early life in China, except that he had a wife and children and learned something about Chinese herbal medicine. He arrived in John Day, Oregon around 1887 and settled in its Chinatown, which housed some 2,000 laborers working in the hydraulic gold mining operations in Canyon City.

The same year, John Day became the home of another Cantonese (Guangzhou was then called Canton, lending its name to the region of southern China and the Chinese dialect), Lung On. Lung was from a wealthy family and well-educated, with a flair for business. Like Ing, he left behind a wife and children in Guangdong.

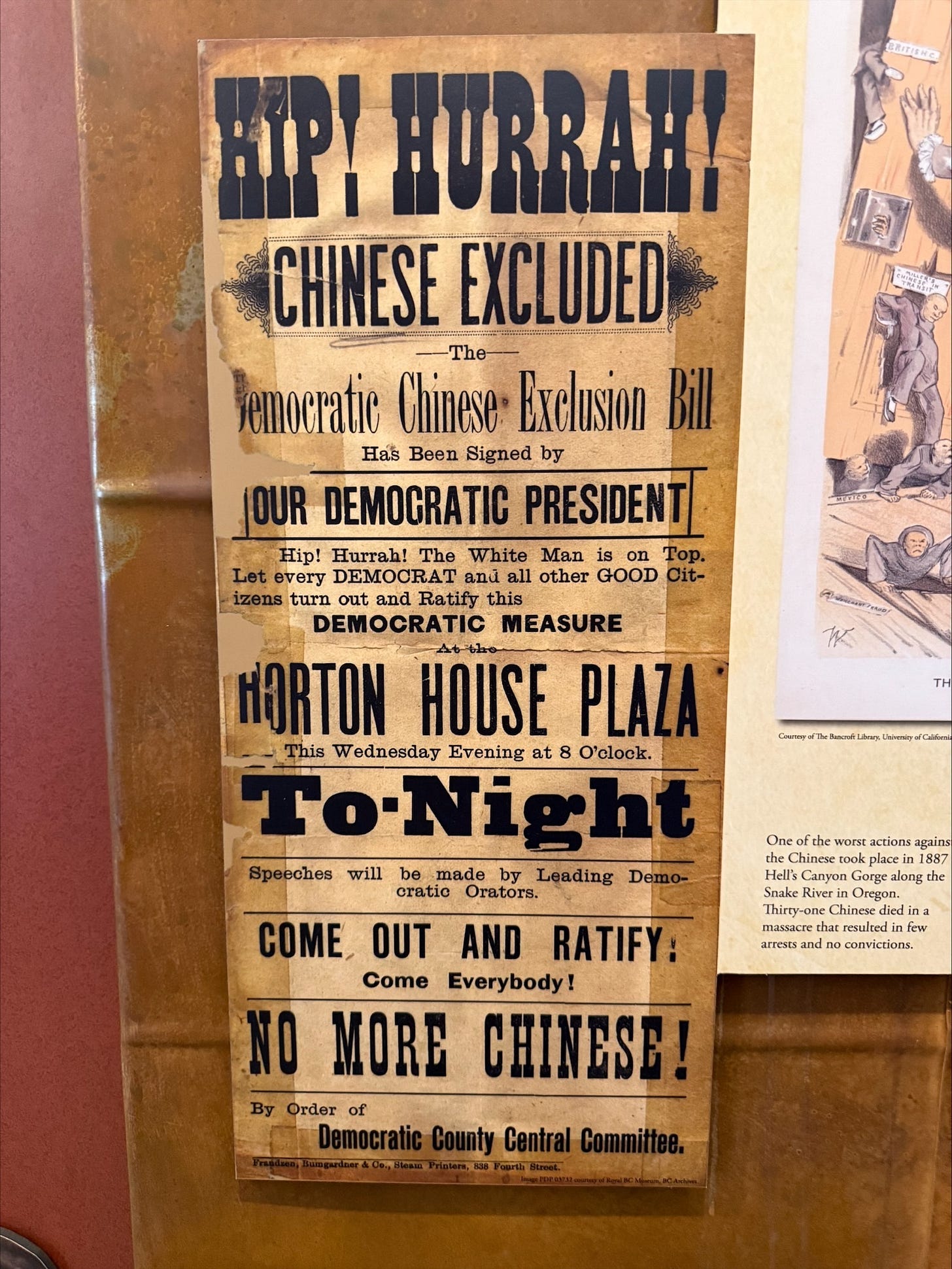

Ing and Lung’s presence in Oregon was very likely illegal. Many American workers, especially those in the West, where Chinese laborers were most common, resented the Chinese presence, arguing they took jobs from Americans and corrupted the culture. Democrats initially spearheaded the drive to exclude Chinese laborers, but it was Republican Chester A. Arthur who signed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 into law. The Act banned Chinese laborers from entering the U.S. and prohibited Chinese from becoming U.S. citizens.

John Day and nearby Canyon City were booming in 1887, and newcomers Ing and Lung bought a business in the heart of John Day’s Chinatown, Kam Wah Chung & Co. The business occupied a two-story building anchoring the teeming slice of Guangdong in Grant County.

Kam Wah Chung was something of a community center for the local Chinese population. There, Ing plied his trade as a pulsologist, using a patient’s pulse to diagnose what ailed him, and as an herbalist, treating the ailment with brews made from his 500-some Chinese herbs and “various animal parts,” according to placards at the site today.

Lung stocked the place with American and Chinese goods and hosted gambling games of unknown type, often shrouded in opium smoke. It seems many Cantonese in Oregon in those days kept the habit that led to the wars that helped make their home on the South China Sea untenable.

By the turn of the century, the Canyon City mining operations had largely exhausted the easily-accessed gold, and the demand for labor dropped. Many of John Day’s Chinese population moved elsewhere, including to Portland, where job opportunities abounded in comparison to the rugged, isolated John Day River valley.

Yet Ing and Lung stayed on in John Day, gradually shifting Kam Wah Chung’s offerings to serve a largely American audience. Locals called Ing “Doc,” and he developed a regional reputation for curing troublesome conditions. Doc had patients - American and Chinese - throughout the Pacific Northwest. They sent him letters describing their ailment, along with a fee, and Doc sent them herbs to brew their own remedies.

Lung amassed a considerable business empire, owning racing horses, rental properties in John Day and the town’s first car dealership in addition to the sale of goods out of Kam Wah Chung.

Despite their questionable legal status (noncitizen voting was then relatively common and legal in some U.S. states), Doc and Lung were both registered to vote in Grant County as Republicans and voted regularly, according to a tour guide at Kam Wah Chung during a recent visit. The entrepreneurs remained involved in Chinese politics too, supporting Chang-kai Shek’s Nationalist Party against the Chinese communist revolutionaries of Mao Zedong.

Lung died suddenly in 1940 at the age of 78 and is buried in John Day. Doc fell into a deep and prolonged depression following the death of his friend and business partner. Doc himself, by then blind, fell and broke his hip in 1948, necessitating a surely excruciating car ride to a Portland hospital. Doc left the hospital, but not Portland, dying from pneumonia in a nursing home there in 1952.

Doc was buried in John Day, next to his friend Lung On. Neither one ever saw his Chinese family again after leaving Guangdong for Oregon. At their deaths, Doc and Lung were among the best-known and successful residents of John Day.

When Doc left John Day for what ended up being the last time in 1948, Kam Wah Chung and its contents were locked up tight. It remained sealed until a John Day city councilor entered the building, by then owned by the city, in 1967. Remarkably, the dry climate and lack of intruders left the place a kind of time capsule, with wares for sale, furnishings and even Doc’s food pantry pristinely preserved.

A National Register of Historic Places plaque on the Kam Wah Chung building says it is “the best and earliest known example of a Chinese mercantile and herb store in the United States.”

Kam Wah Chung is now owned and maintained by Oregon State Parks. Visitors can peruse a nearby interpretive center with tours of Kam Wah Chung itself held more or less on the hour. Staff suggests calling ahead to make sure about the tours.

Great story and background context! A few small but interesting facts. When the Kam Wah Chung was finally reopened the FBI wanted in asap as they believed that there was till Opium inside the store and wanted to do a clean sweep of the place to make sure. Many of the parcels in the store from China remained unopened at that time and I believe are still sealed. The City also found a few cases of pre-Prohibition whiskey and those cases were taken off to the Grant County Courthouse for "safe" keeping!

Nice write up on these two fascinating gentlemen.