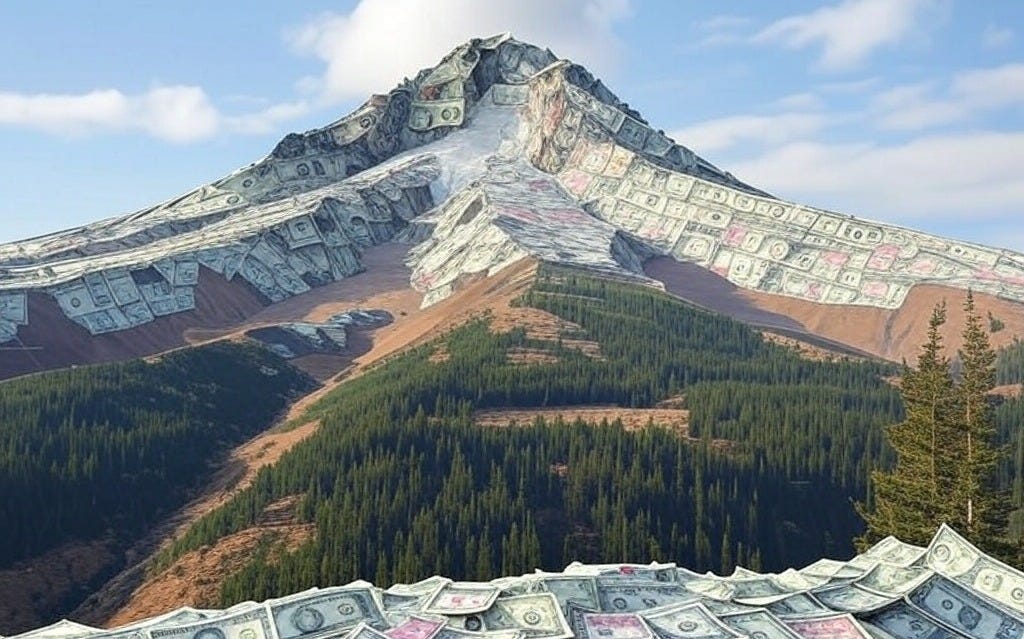

Oregon continues to climb the tax mountain

Even as businesses and individuals flee the state, Oregon continues to look for ways to pile on more taxes

Just how high are Oregon taxes? That’s a hard question to answer, in part because there are a lot of ways to measure tax burden, but even more so because Oregon has so many taxes it’s hard to identify them all and add them up. And the problem is worse in Portland.

The Tax Foundation, which tracks taxes and tax policy nationwide, did a report on Portland’s taxes last year. It identified 9 different income-based taxes that individuals and businesses must pay. It ranked Portland in the top 3 in the nation (often No. 1) for both personal and business taxes under a variety of circumstances. The list does not include the gas tax, arts tax, clean energy surcharge and several lesser-known taxes that are assessed only on certain taxpayers (usually big businesses) or based on factors other than income. So, it actually understated how much you have to pay for the “privilege” of living in Portland.

And here’s even scarier news: Facing and uncertain economy and tight budgets, the Oregon Legislature is considering a more taxes dedicated to specific needs and causes.

The proliferation of specialty taxes and fees is bad for many reasons, but two stand out:

First, government leaders like to attach taxes to specific issues because it’s easier to gain support when they money goes directly to a service voters use than when it goes into the general budget. But no matter how popular the causes to which the taxes are dedicated, you eventually reach a tipping point where businesses and residents say, “that’s too much” and leave. It appears Portland has reached that point as businesses and individuals flee the city.

Speciality taxes do something else that’s less noticeable but perhaps more important: They hide the true tax burden from just about everyone but tax accountants and government revenue departments. The lack of easily accessible numbers about tax burden restricts public debate and adds to taxpayers’ frustration and suspicion about government.

A good first step would be to agree not to create any new taxes. But Oregon’s ruling Democratic Party clearly is not ready to make that decision. Consider two of the new taxes currently being discussed - each indicating a key problem with targeted taxes.

Tire tax: House Bill 3362 imposes a 4% tax on retail tire transactions in the state with revenue “to be allocated between public rail transit and tire-related pollution reduction and mitigation efforts” among other things. The best thing that can be said about this proposal is that Oregon’s transportation-funding system is broken (a problem shared by many states) and someone needs to come up with a new idea.

However, taxing tire-buyers for public transit is, at best, an indirect route to the end goal, and, at worst, a thinly disguised attempt to penalize those who prefer driving to using mass transit. The Republican alternative to this approach is to drastically reduce mass-transit funding. That’s more in line with consumer demand but politically impractical in a deep-blue state. This newsletter has pointed out the flaws in the tire tax since it was first proposed, but we’re also realistic about the likelihood of Democrats accepting a no-new-taxes alternative.

Timber severance tax: House Bill 3489 would change the timber severance tax so it is assessed based on value instead of on log value. The money would go toward fire protection. Proponents say the goal is to “fairly” tax real estate investment trusts and other out-of-state landholders who contribute to fire danger (by owning trees) but don’t pay their fair share toward forest-fire protection. Leaving aside the question of what “fair” is, this change clearly is driven by a desire to increase revenues in the most politically expedient manner possible.

This approach consistently has gotten Oregon into trouble, because what is politically expedient does not necessarily deliver the desired results. Politicians call this “unforeseen” consequences. In truth, the consequences usually are easy to predict. In this case, logging - already financially challenging - would become even more expensive in Oregon. A loss of jobs and higher timber prices are at least possible - if not likely. And it’s quite possible that in at least some cases decreased logging would increase fire risk.

Where does all this leave Oregon? We’re either hoping for a miracle, whether that’s surprisingly strong economic performance or Democrats curbing their tax addiction, or destined to see more businesses and individuals decide Oregon isn’t worth the price.

Oregon doesn’t have a sales tax, but when you buy a new car, they charge you a “dealer opportunity fee”, which is in reality a tax. democrats think that by changing the wording, that somehow changes the reality of their tax and spend philosophy. i’ve been dreaming of the day when my wife passes on, so I can move to a state that doesn’t tax the hell out of my retirement. Then I’ll be another one of those people that left, but Salem won’t notice because permanent government employees who have never worked in the private sector, have no concept of economics or keeping to a budget.

One would think the current plight of the City of Portland and MultCo with Taxpayer/business flight would act as a cautionary tale but with democrats it seems to be an encouragement